Release date: 27 October 2022 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

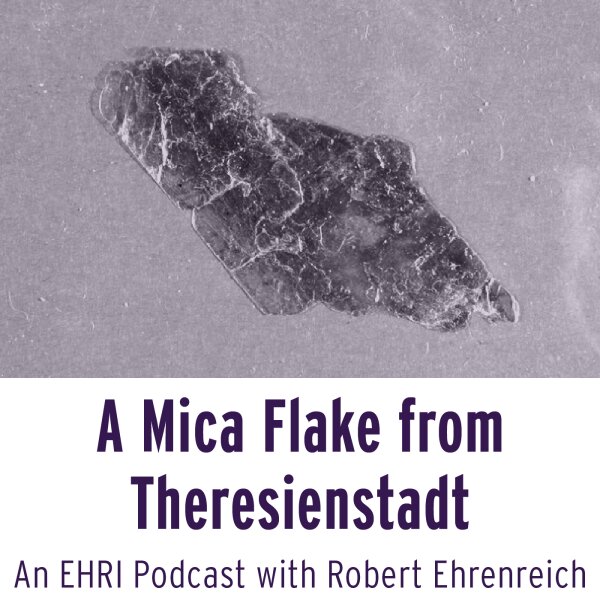

In this episode, we will talk about mica-flakes, objects of little monetary value that were kept by survivors from the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Also known as glimmer, the flakes, shiny glass-like, thin mineral sheets, were sliced from rocks with razor sharp blades by the women of the ghetto under forced labour conditions.

On the one hand the flakes are a symbol of beauty, on the other of persecution and the ever present threat of not only food penalties beyond the normal rationing but, deportation to the gas chambers in Auschwitz, should the women make a mistake.

Several of these mica-flakes are now in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, donated by the survivors or their children. Robert Ehrenreich, who works for the museum, has done extensive research into the mica-flakes and the stories of the women who kept them after their liberation from Theresienstadt.

Featured guest: Robert Ehrenreich, Director, National Academic Programs, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Podcast host is Kevania de Vries-Menig.

The views expressed in this podcast are those of Robert Ehrenreich and do not reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Robert will tell the story of Emma Jonas and her mica-flakes that came into the collection of the museum. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts or here:

“This is the mica—Glimmer—it’s like plastic. It’s like thin layers of plastic. [...] They must have had some plans to use it, but in the meantime, it saved my life and it saved my mother’s life when she got to work in there.”

From a testimony by Hilda Stern (USC Shoah Foundation)

Hilda survived the Holocaust in the Theresienstadt Ghetto, where she was forced to slice up minerals, known as mica-flakes or glimmer.

Mica-flakes are ultrathin, irregularly shaped sheets that are either clear or slightly brownish with some striations. Mica is an excellent electrical insulator and was used by the Luftwaffe to keep vacuum tubes in radios from shorting out. Women like Hilda Stern were forced labourers in the Glimmer Werke, or mica-splitting factory near Theresienstadt in German-occupied Czechoslovakia. Although the working conditions were harsh, it gave the women some food, shelter and, and to a certain extent protection against transportation. Most women in the group, where they could support each other, survived the war.

Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt was a ghetto, but had features of a transit camp. It was used as a temporary holding place for Jews on their way to camps further east.

The town of Theresienstadt, or Terezín in Czech, was built around a military fortress, constructed in 1780. Until the Nazi occupation, the town had an average population of just under 4,000 people.The Nazis established the ghetto on 24 November 1941. Following this, an average of 35,000 people were incarcerated at any given time between 1941 and 1945.

From the start, Theresienstadt was intended to serve as both a holding site for Jews on their way to extermination camps in the east or for Jews of cultural or political fame until their eventual deportation or death. Later, Theresienstadt was also an important propaganda tool to disguise the nature of the Nazis treatment of elderly or prominent Jews. Nevertheless, conditions for prisoners held inside Theresienstadt were very poor. Of the 140,000 prisoners who were imprisoned there during its existence, 33,000 perished at the ghetto due to deprivation, starvation, and disease.

Robert Ehrenreich and his research

Dr. Robert Ehrenreich has worked for the US Holocaust Memorial Museum since 1999, where he heads its National Academic Programs, which promote understanding of the Holocaust across North America through multidisciplinary research, teaching, scholarly forums, and publications. His current research focuses on the material culture of the Holocaust, the study of the things that people created, hid, obtained, and repaired to provide insights into their lives and this history.

Dr. Robert Ehrenreich has worked for the US Holocaust Memorial Museum since 1999, where he heads its National Academic Programs, which promote understanding of the Holocaust across North America through multidisciplinary research, teaching, scholarly forums, and publications. His current research focuses on the material culture of the Holocaust, the study of the things that people created, hid, obtained, and repaired to provide insights into their lives and this history.

Robert Ehrenreich became interested in the mica-flakes, when he learned about them from a colleague at the museum, with whom he was writing an article. The flakes were donated to the museum in 2004 by Helga Carden, daughter of Emma Jonas, a survivor of Theresienstadt. In 2016, a second set of flakes were donated. Robert was intrigued and found out that another, earlier set was also in the collection of the museum since 2006. One set was interesting, but three sets showed that something deeper was going on. This led him down the rabbit-hole of studying the material culture of the Holocaust. He researched the stories of the three women who had kept the mica-flakes after the war and looked into their reasons for taking some mica-flakes with them after the liberation.

Learn More

- Mica flakes cut by a German Jewish female slave laborer (Emma Jonas), US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Flake of mica collected from Theresienstadt by a German Jewish factory worker (Selma Ansbacher), US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Two pieces of mica from a forced laborer in a glimmer factory (Ilse Silten), US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Testimony by Hilda Stern, from the USC Shoah Foundation

- Robert Ehrenreich (US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- Theresienstadt Ghetto (from The Holocaust Explained)

- Theresienstadt (from the Holocaust Encyclopedia, US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- Czechia in the EHRI Portal

- Terezín Memorial

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- Robert Ehrenreich. The views expressed in this podcast are those of Robert Ehrenreich and do not reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Fragments of the Interview of Jerry Rosenstein are courtesy of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Interview of Hilda Stern is from the archive of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education. For more information: http://sfi.usc.edu/

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks - Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14