New Online Edition: “From Vienna to Nowhere: The Nisko Deportations 1939”

By Wolfgang Schellenbacher (Vienna Wiesenthal Institute)

The Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance (DÖW) is pleased to have created a new online edition to add to the growing number of innovative digital EHRI Editions. The online document edition “From Vienna to Nowhere: The Nisko Deportations 1939” brings together documents from the Archives of the Jewish Community in Vienna (IKG), the DÖW, the Arolsen Archives, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the Vienna Regional Court. The edition (which is in German) will continue to be expanded upon and updated with new documents, using the innovative digital presentation tool of the Online Document Edition to assist scholars in further researching the Vienna transports to Nisko and the fate of these Viennese Jews deported to Eastern Poland - and serve as a foundation for new research questions.

Fate of the deportees

As with all EHRI online editions, “From Vienna to Nowhere” links to the collection descriptions in the EHRI portal, as well as offering users the option to read all documents and also access them via maps and visualisations. In addition to a full-text search of all documents, the edition contains short introductory texts and indexes that allow the edition to be searched and automatically rearranged according to the reader's interests. Research into the Nisko Action has long focused on the history of the transports as a trial run for the later mass deportations of the Jewish population. The online edition contains documents detailing the history of the transports, but also focuses on the fate of the deportees and their experiences; including a list of all those included on the Nisko transports, compiled and published for the first time. The names of those who died in the Holocaust are linked to the DÖW database of victims. Furthermore, short biographies of more than 150 deportees whose names appear in the edition documents have been compiled.

Personal Documents

Rare personal documents of the deportees form the core of documents in the edition: The most important source is the correspondence of the deportees with the Jewish Community in Vienna, now held in the archives of the IKG (Jerusalem holdings). These letters give an insight into the fate of the 1,600 men deported from Vienna, how their desperate situation unfolded and their "everyday life" between autumn 1939 and March 1940. A large number were expelled upon arrival and tried to flee across the German-Soviet demarcation line. Others stayed in the area between Nisko and the demarcation line and depended on Jewish aid organisations.

Siegmund Flieger

On 13 December 1939, Siegmund Flieger wrote from Bełżec to the Jewish Community in Vienna asking for help on behalf of 35 men who had been deported from Vienna to Nisko in October 1939:

"Our people are sick, completely exhausted by hunger and hardship, we are starving and freezing without any warm clothes, and we are living among a population that is unfriendly to us and from which we not only cannot expect any support, but which also continues to hinder us. We can't go back or forward, because all borders are hermetically sealed for us.”

Siegmund Flieger was born in Vienna in 1902, the son of Jacob Herz Flieger and Agathe Flieger née Bellak. He worked as a waiter and lived at Schrottgießergasse 3 in Vienna's Leopoldstadt district. In May 1938, he filled out an emigration questionnaire at the Jewish Community in Vienna in the hope of being able to arrange his emigration to North or South America. His wife Ernestine, born in Bruckmühl in 1902, was interned in the collection camp at Gänsbachergasse 3 for a planned third Nisko transport. After Siegmund Flieger, like most of the deportees, had been expelled from the Nisko area, he arrived in Bełżec with a group of Viennese deportees, from where he contacted the Jewish Community in Vienna.

In April 1940 he was one of almost 2000 of the deportees who were able to return to Vienna. On 1 May 1943 he was deported again, this time with his wife and daughter to Theresienstadt and from there to Auschwitz in September 1944. On 26 February 1945, via Sachsenhausen, he reached Mauthausen, where he was liberated. His wife and daughter were murdered in the Holocaust. Siegmund Flieger remarried and emigrated with his family to Brazil in 1950.

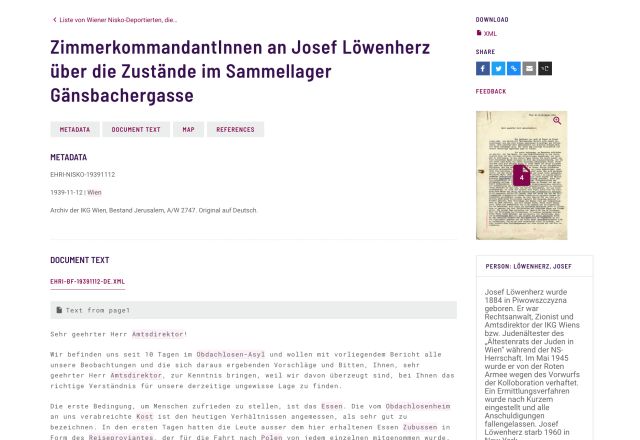

Prisoners of the Jewish Community

Documents from the holdings of the Jewish Community in Vienna are also able to shed light on conditions in the collection camp in Gänsbachergasse, where men women and children were interned for a third Nisko transport – a transport that never left Vienna in the end. The history of the collection camp and the third transport was described by Dieter Hecht in an introductory text in the edition. A description by the room commandant of the collection camp on 22 November 1939 shows the desperate situation of these Jews and also illustrates conflicts with the Jewish Community in Vienna:

“[...] we have realised that by appointing external security guards, people have the feeling of being inmates. It is therefore inevitable that people grumble and are of the opinion to be prisoners of the Jewish Community.”

Rafaela Huschak

One of the signatories was Rafaela (Rachela) Huschak née. Flat. She was born in 1895 in Fryštát and in 1920 married the chauffeur Leo Huschak in Vienna, who was one year younger than her. They had two children, a daughter Margarete born in 1921 and a son Hans born in 1927. At the time of Austria’s annexation to Nazi Germany, the family lived in a one-room apartment in a municipal apartment complex on Troststraße 68–70 in Vienna, Favoriten.

At the end of June 1938, the City’s Housing Office issued around 2,000 termination proceedings against Jewish tenants in communal flats. Leo Huschak and his family also lost their apartment on 31 July 1938. Although the family managed to receive an extension of the eviction period, they had to leave the apartment at the end of October 1938 and move to a shanty town in Vienna.

In the following months the family looked in vain for emigration opportunities to Colombia, Palestine or Shanghai. On 20 October 1939, Rafaela Huschak’s husband was deported to Nisko, where all trace of him is lost. From the beginning of November 1939, she was interned along with her children in a collection camp on Gänsbachergasse and was due to be deported on the third transport from Vienna to Nisko. Although the transport was canceled, the internees were not allowed to leave the collection camp until 8 February 1940. Prior to their eventual deportation to Opole on 15 February 1941, Rafaela Huschak was living with her children at Servitengasse 5/16 in Vienna Alsergrund. Rafaela, Margarete and Hans Huschak were murdered during the Holocaust.

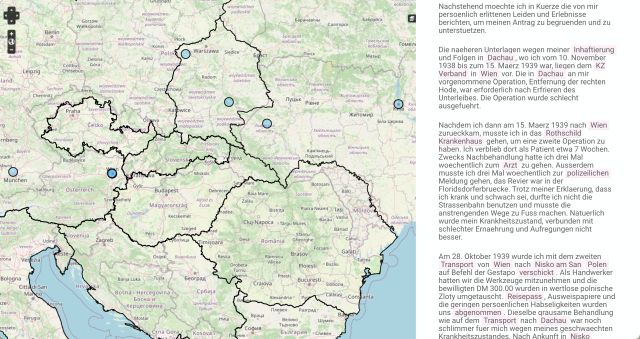

Nowhere

Supplementing the information provided by the correspondence from the archives of the Jewish Community in Vienna are descriptions from the few survivors contained in the Victims' Welfare files (Opferfürsorgeakten), which detail their deportation, expulsion and imprisonment in Soviet gulags. The documents also illustrate the relatively minor role played by the town of Nisko in the experiences of those on the Vienna-Nisko transports. As the digital maps in the online edition show, the large space between Nisko and the Soviet-German demarcation line - which was perceived as a ”nowhere” or a “no man's land” - played a more significant role for the deportees than the camp in Zarzecze near Nisko, where only a small number of the men were imprisoned.

Unexplored chapters

Documents included in the online edition also refer to completely unexplored chapters like the deportation of Austrian Jews from the internment camp Eibenschütz (Ivančice) in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia to Nisko. Correspondence from the Arolsen Archives concerning the fate of Josef Schloss shows this: On 13 December 1939, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) asked the German Red Cross about his whereabouts. The German Red Cross passed the request on to the Gestapo. Josef Schloß was born in Vienna in 1916, the son of textile entrepreneurs Victor and Malvine Schloß. He lived with his parents at 8 Weißgärber Lände, Vienna, Landstraße. At the end of November 1935 he moved to Brno where he lived at 7 Altbrünnergasse and worked for the textile company Aron & Jakob Löw-Beer. On 8 July 1939 he was admitted as a foreign refugee to the Ivančice camp. On 13 April 1940, the Gestapo in Berlin replied to a request from the Red Cross: “

The Jew Joseph Schloß was interned from 8 July 39 to 26 October 39 in a labour camp for Jews in Eibenschitz near Brno, which had been purchased from the funds of the Jewish Community of Brno. On 26 October 1939 he was deported to Nisko in the General Government”.

The fate of Josef Schloss is unknown. His parents Viktor and Malvine Schloß and his sister Olga Pisinger survived the Holocaust in exile in the United Kingdom.

Nazi documents

Nazi documents relating to the organisation of the Nisko Action and the handling of the transports have been included in the online document edition from the archives of the DÖW and the Vienna Regional Court. These documents show, for example, Adolf Eichmann's search for a suitable deportation destination, or how Jewish functionaries from Vienna and Prague (Berthold Storfer, Julius Boschan, Richard Friedmann, Benjamin Murmelstein, Jacob Edelstein, Maurycy Moses Grün) had to take part in the first Nisko transport on Eichmann's orders.

We invite you to visit the Online Edition “From Vienna to Nowhere: The Nisko Deportations 1939” (nisko-transports.ehri-project.eu) and see how the EHRI Online Tools have been implemented to create new insights into this otherwise underrepresented series of events: nisko-transports.ehri-project.eu. This online edition is in German.