Release date: 19 October 2023 | More about the Podcast Series For the Living and the Dead. Traces of the Holocaust

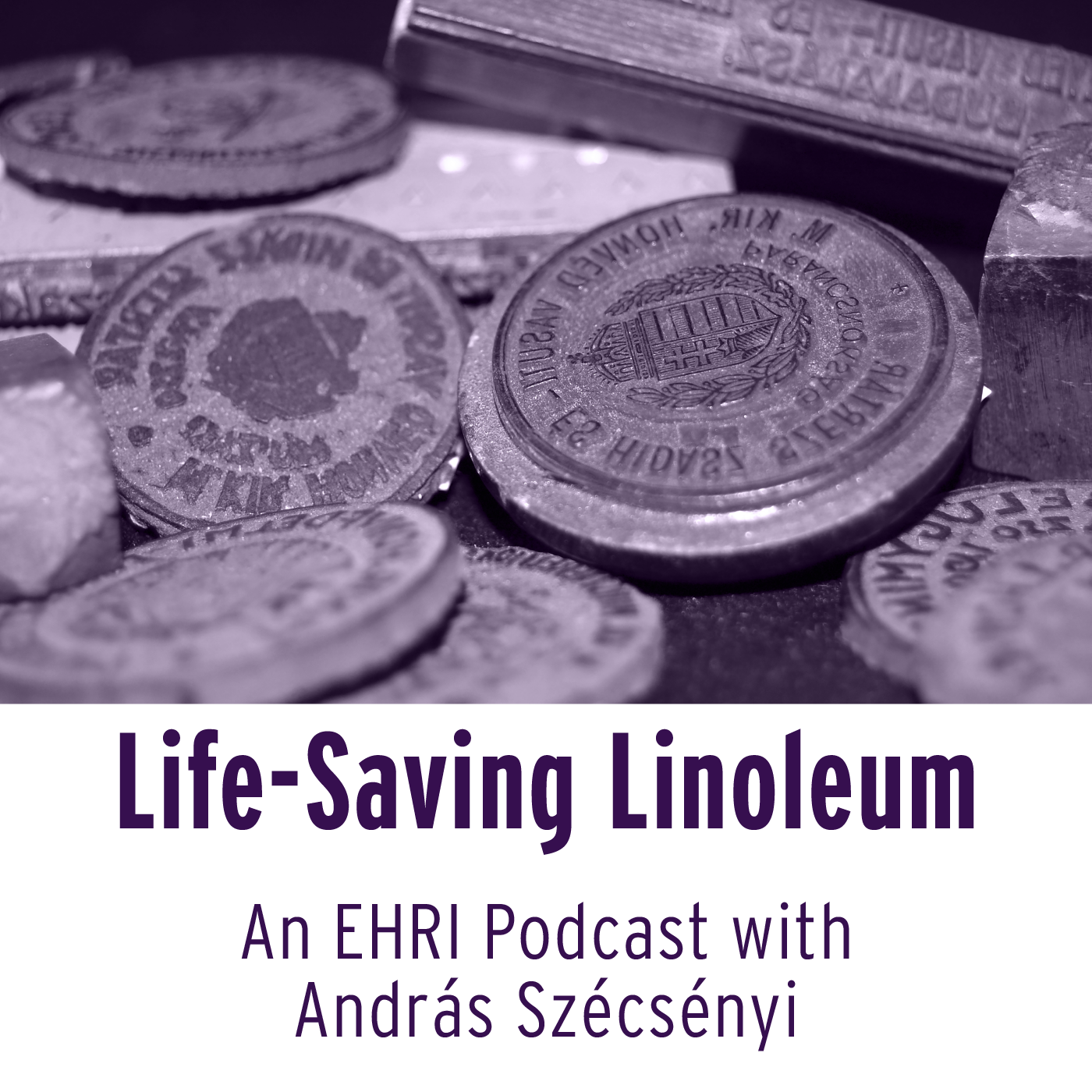

In Life-Saving Linoleum, we talk about a seal forged out of linoleum by a man named Endre Káldori. We hear about how Káldori, with the watchmaker skills he learnt from his grandfather, a simple piece of linoleum, much luck, and an incredible amount of daredevilry, saved many family members and friends.

Hungary joined the Axis Alliance in November 1940 and eventually, together with Germany, entered the state of war with the Soviet Union in June 1941. Following the catastrophic losses at Stalingrad between 1942-43, the Hungarian regent tried to take the side of the Western Allies, but German troops occupied Hungary in March 1944.

The situation of the Hungarian Jews became increasingly difficult. Racial laws were passed between 1938 and 1941 and many Jewish men were forced into labour service. Initially, however, Hungarian Jews lived in relative safety as the Hungarian authority only targeted non-Hungarian Jews, but after March 1944, Hungarian Jews were also deported and killed, or isolated in special houses and ghettos. Endre did everything he could to save the lives of his family and those nearby. With a great amount of bravery, he forged documents and seals that helped people to get out of dangerous situations.

Copyright: Holocaust Documentation Center

and Memorial Collection Public Foundation

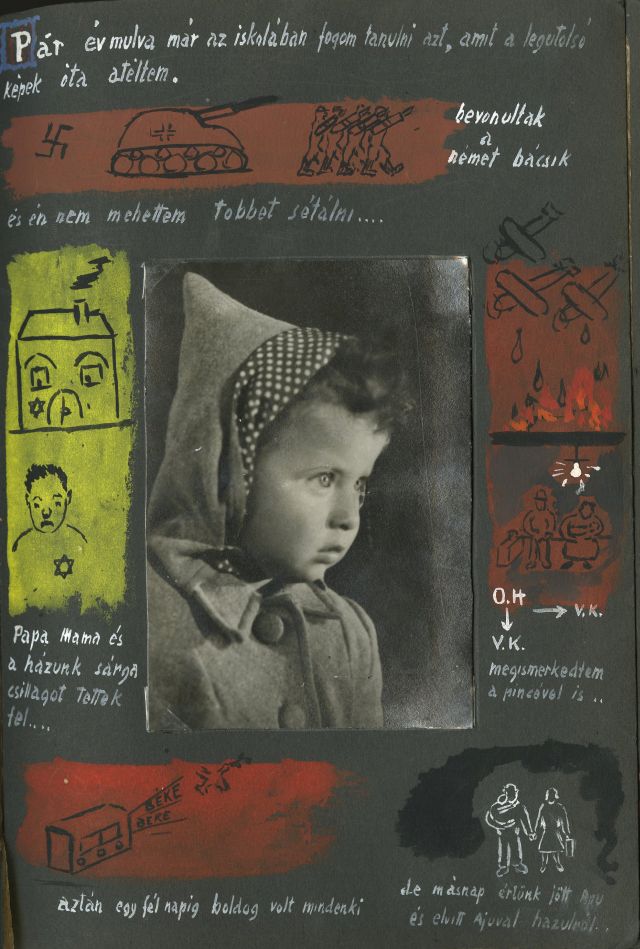

The seal is now part of the Endre Káldori Collection, a unique collection of written documents, photos and objects, in the archive of the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest. The collection consists of the hand-made linoleum seals, fake papers, blank forms of certificates, fake birth certificates etc. A unique object in the collection is a photo album. The album is full of photos and drawings prepared by Endre Káldori for his daughter Zsuzsanna and tells the story of the family's hiding during the Holocaust and the liberation.

Featured guest:

András Szécsényi is a research fellow in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security in Budapest and holds a Ph.D. degree from ELTE (Budapest). He has worked as Head of Collections in the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest between 2005 and 2017. Podcast host is Kevania de Vries-Menig.

András will tell the story of the seals and Endre Káldori. Listen to the episode on Buzzsprout, Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or here:

“First of all, it should be mentioned that my father had very good manual dexterity. His grandfather was a master watchmaker and everyone else had good manual dexterity in our family. So the fact that my father could forge technically, he obviously found out very quickly. And then there was his personal courage. He was a boy scout as a child, a member of the Jewish scout troop. From there he had some friends who were brave, tough boys like himself. My father socialized in this circle and these cool, tough Jewish guys remained friends in his adult life, and he maintained a good relationship with them. They were always trying to do something to save their families. I think their behaviour, their attitude, must have encouraged my father to do something. But only my dad made seals.”

Gábor Káldori about his father Endre, in an interview by the Holocaust Documentation Center and Memorial Collection Public Foundation, Budapest, Hungary.

Copyright: Holocaust Documentation Center

and Memorial Collection Public Foundation

Born in 1919, Endre Káldori started learning his trade at the age of fourteen in his uncle’s repair workshop for writing utensils. He married in 1941 and the couple lived in Budapest at the time of the war. Until 1944, life for Hungarian Jews in Budapest was difficult, but relatively safe. They were excluded from society by anti-Jewish legislation and the men were often forced into hard labour. Endre Káldori however had an optimistic nature and found the labour into which he was forced, together with many Jewish friends, almost an adventure.

When the situation in Hungary changed and the Nazis took over, the deportations and killings of Hungarian Jews started, first with the exemption of Budapest.

Copyright: Holocaust Documentation Center

and Memorial Collection Public Foundation

Inspired by the group of Jewish friends Endre had worked with before and who had decided that they would protect themselves, family and loved ones as well as they could, Endre found the bravery to put his technical skills to use and set up a small forgery in his home. The documents, seals, blank forms he forged saved most of his family and inner circle in Budapest. With official resistance organisations, he had no contact, he was very much his own man.

From the end of June 1944, Jews had to live in so-called “yellow star houses”, as did Endre with his wife and new-born daughter, but Jews in Budapest were initially spared from the deportations to Auschwitz.

Copyright: Holocaust Documentation Center

and Memorial Collection Public Foundation

The persecution of Jews was resumed on 15 October, when the Arrow Cross Party came to power. Armed party militias killed thousands of Jews in the streets of Budapest, and tens of thousands were drafted for forced labour. The remaining Jews were forced to move to sealed-off ghettos. Endre and his family managed to stay outside of the ghetto by hiding in several places. At the last stage of the war, they hid in their own house, where they were liberated in January 1945 by the Red Army.

Hungary became a communist state to which Endre Káldori adapted with the same brave spirit. He took up his old trade of repairing writing utensils. To his two children, Zsuzsanna and Gábor, he never talked much about this activities in the war, until much later. Zsuzsanna and Gábor donated the collection of their father’s legacy to the Holocaust Memorial Center.

Hungary in the war

Hungary fell increasingly under the influence of Germany as the Nazi regime consolidated itself during the 1930s. When Germany began to redraw national boundaries in Europe, Hungary was able to regain territory. In November 1940, Hungary joined the Axis alliance. On 27 June 1941, Hungary declared war on the Soviet Union. After Germany’s defeat at Stalingrad and other battles in which Hungary lost tens of thousands of its soldiers, the Regent of Hungary, Miklós Horthy, initiated clandestine peace negotiations with the Western Allies. As a result, German troops occupied Hungary on 19 March 1944. However, Horthy was allowed to remain regent. Following a thwarted attempt to exit the war, on 15 October 1944, Horthy was replaced by the fascist Arrow Cross government. The German occupiers were driven out of Hungary by the Red Army on 13 April 1945.

According to the 1941 census, Hungary with its annexed territories had a total population of about 14 million, including 725,000 Jews, among them 400,000 in Hungary proper, and tens of thousands of Christians who were considered Jewish by racist criteria. From 1938 onwards, anti-Jewish legislation effectively excluded the Jews from Hungarian society depriving them of many civil rights and economic opportunities. Jewish men were forced to perform unarmed military labour service in the Hungarian Army. Thousands of them perished on the Eastern front.

Despite serious casualties and the increasingly antisemitic political climate, most of the Hungarian Jews could live in relative physical safety until March, 1944. However, after the German invasion, a large part of Jewry in Hungary was murdered. Due to the smooth cooperation of the Hungarian government, public administration, and law enforcement, the German authorities were able to deport nearly all the Jews from the provinces, close to 440,000 people, over a period of only 56 days between May and July 1944. With the exception of some 15,000 people who were sent to labour camps near Vienna, all the deportees were taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where about 75% of them, mostly women, children and the elderly, were murdered in gas chambers upon arrival; the others remained in Auschwitz or other camps.

According to the Germans’ plans, the approximately 200,000 Jews of Budapest were next in line to be locked into ghettos and then deported. From the end of June 1944, they had to live in so-called “yellow star houses”. Jews in Budapest were spared from the deportations to Auschwitz. The persecution of Jews was resumed on 15 October, when the Arrow Cross Party came to power. Armed party militias killed thousands of Jews in the streets of Budapest, and tens of thousands were drafted for forced labour to build fortifications at the south-eastern border of the Greater German Reich in Austria. The remaining Jews were forced to move to a sealed-off ghetto in early December, whereas a so-called international ghetto was established for Jews with passports or protective documents issued by embassies of neutral countries. On 18 January, the Red Army liberated the ghettos. In Budapest, some 150,000 Jews survived in the two ghettos and in hiding. Between 1941 and 1945, more than half a million people, that is, two thirds of the Jewish population of the wartime territory of Hungary, were murdered by the Nazis and their Hungarian collaborators.

András Szécsényi

András Szécsényi is a research fellow in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security (Budapest) and holds a Ph.D. degree from ELTE (Budapest). He has worked as Head of Collections in the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest between 2005 and 2017. He is currently working on a research project about the history of the Hungarian inmates of Bergen-Belsen (1944–1945) and its political-societal contexts.

András Szécsényi is a research fellow in the Historical Archives of the Hungarian State Security (Budapest) and holds a Ph.D. degree from ELTE (Budapest). He has worked as Head of Collections in the Holocaust Memorial Center in Budapest between 2005 and 2017. He is currently working on a research project about the history of the Hungarian inmates of Bergen-Belsen (1944–1945) and its political-societal contexts.

While working for the Holocaust Memorial Center, he came in contact with Zsuzsanna Káldori, the daughter of Endre, who donated the collection to the Center. The story of the collection and Zsuzsanna have made a lasting impression on him.

Learn more

More about Endre Káldori in an article written by András Szécsényi, “Lebensrettendes Linoleum”, in: Nur eine Quelle… (S.I.M.O.N., VWI, 2014) p.210-214.

Hungary in WW2 in the EHRI Portal

Arrow Cross Party in the EHRI Portal

Holocaust Documentation Center and Memorial Collection Public Foundation, Budapest, Hungary

Credits

Our thanks go to:

- András Szécsényi

- László Csösz, Senior Archivist Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives, for his help and his voice-overs

- The Káldori family, Gábor and Zsuzsanna

- Holocaust Documentation Center and Memorial Collection Public Foundation, Budapest, Hungary

- Music accreditation: Blue Dot Sessions. Tracks - Opening and closing: Stillness. Incidental, Gathering Stasis, Pencil Marks, Uncertain Ground, Marble Transit and Snowmelt. License Creative Commons Atttribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (BB BY-NC 4.0).

- Andy Clark, Podcastmaker, Studio Lijn 14